Hip Stability - The Precursor to Deceleration & Reactive Agility Training

Rapid change of direction is required and demonstrated consistently by elite level athletes. The ability to rapidly decelerate and change direction requires and athlete to perform a variety of skills at any level of performance. These trainable aspects range from neuromuscular coordination at both the hip and the foot, strength, an efficient stretch-shortening cycle for reactive ability (transition from eccentric to concentric muscle action), etc. Looking back to some of the most exciting professional athletes to watch, Barry Sanders sticks out in my mind. If you haven’t seen him play, simply go to YouTube and search for his highlights, you will not be disappointed. Sanders was consistently able to demonstrate stability, as well as strength, all combined in a fluid movement in an ever changing environment.

When each of these aspects are highly trained the athlete learns to “cut on a dime”. As coaches we must approach this training of change of direction in a logical progression. If we improperly implement certain aspects of this ability prior to others, our athletes are likely to have less successful transfer from this training. For example, if an athlete is not capable of completing the rapid deceleration portion of this movement in a controlled manner, potential for injury is dramatically increased while maximal agility is diminished.

Again, each of the aspects named above (neuromuscular coordination of hip and foot, reactive ability of muscles, etc.) are extremely important in the ability to rapidly change direction. Referring back to Barry Sanders, he demonstrated each these abilities in an extremely violent and rapid fashion. With all of these trainable abilities, a critical factor remains one of, if not the most, important to teaching change of direction: hip function and stability. Hip function and the ability to stabilize in all three planes of motion is absolutely critical to both safe and effective cutting and agility. If Barry Sanders were to lack this ability, he never could have become one of the most elite and exhilarating running backs to ever play in the NFL.

When an athlete does not possess the ability to stabilize through their hip, that athlete will eventually break down and suffer an injury. If enough repetitions are completed with a lack of tri-planar hip control, they will break down and an injury will occur due to compensation patterns. This becomes particularly important in elite level performance as the body is required to thrive in and endure many multiple rapid and violent changes in direction. It is important coaches train athletes appropriately starting with the most basic abilities and progressing into the more “advanced” high-velocity movements, once the aspects of the glute layering model have been addressed.

Deceleration drills are a great example of this, and are commonly utilized by many coaches. These exercises have their time and place within a program and can be great tools for teaching deceleration. If the athlete being trained is deficient in the appropriate abilities to stabilize their hips and pelvis in a single leg stance, they are only reinforcing incorrect patterns that may eventually lead to an injury. By “grooving” the correct movement pattern, a coach efficiently implements proper progressions. This will lead to the athlete mastering correct patterns faster and thus advance to the next hip stabilization phase more quickly. The importance of myelination in skill learning has been demonstrated multiple times, and thus will not be covered in this article. For information on skill learning, click here. Coaches must implement their understanding of appropriate biomechanics in all movements completed to the best of their ability. This is of utmost importance at the hip due to its relationship to the knee.

A “stable” hip in all planes of motion must be achieved prior to implementing movement patterns such as deceleration drills, regardless of the speed they are implemented. Otherwise improper motor patterns or habits will be formed with the hip functioning improperly. This is not saying that the deceleration drills implemented will not be effective. However, the drills will only maximize the deceleration abilities of an athlete who is able to stabilize their pelvis in a single leg stance. Proper progression concepts are king and should be understood to ensure athletes are “learning” skills as efficiently, appropriately, and effectively as possible.

Progression Concepts

Neural Strategy Goals:

- Make athlete “self-aware” (single aspect)

- Create “plasticity” in the brain

- Start single-joint

If an athlete is not able to properly utilize their hip, or “fire” their musculature in a single-joint setting, how will they be able to effectively utilize this joint in a total body movement? The idea of compensation patterns and how the body can find multiple ways to complete a single movement is becoming better understood by coaches. Personally, I take the approach that the hip (or glute) should be the primary driver in the stabilization of the entire chain. If it is not functioning properly, all other joints/tissues will be required to make up for its lack of control. Creating “plasticity” is also utilized in the single-joint manner early to ensure the athlete can consistently utilize the desired muscle (in this case the glutes) throughout the upcoming training session. Coaching of positioning is required throughout this training as athletes are commonly unaware of what they should be “feeling” during each exercise. As the athlete becomes more competent in these movements, the coaching required will begin to decrease.

Increase Stability Goals:

- Make athlete “self-aware” (total body)

- Progress exercises and increase demand

- Continue to “groove” correct patterns

Once neural plasticity has been improved in an athlete through hip priming, the athlete can begin the process of furthering stability throughout training. As always, proper progressions have a tremendous effect on an athlete’s learning ability. Always ensure proper technique and stability prior to advancing progressions. At this point, the athlete should be “self-aware” of their ability to control the hip complex through movement. Since human movement is dynamic in nature and especially in sport, inclusion of gravity and movement are critical within the progression. If strength at certain ranges of motion are needed, implement isometric training at the specific joint angles to enhance an athlete’s technique. Coaching and cuing will still be required throughout this phase as these movements will be relatively new to the athlete. The athlete has now become more comfortable in these movements and aware of the desired pattern of each exercise. Adding impact such as lunging or even small jumping can be included as an athlete demonstrates control capabilities through their hip and pelvis.

Force-Vector Change Goals:

- Make athlete “self-aware” (with landing)

- Require athlete to move through space

These athletes should now be capable of demonstrating control over their hip on a single leg from a vertical jump. If an athlete cannot complete this task under control then they are not prepared to handle this progression. Once they are capable of demonstrating this form of single leg control, coaches are able to change the distance traveled through both horizontal and vertical alterations. The changes in vector require increased proprioception and rate of force absorption at different landing angles. Even in limited repetitions, the training of these different landing angles can continue to provide the athlete with a “strategy” to safely maneuver when these angles are encountered on the field of play. As the athlete begins moving further distances horizontally, the actions required in rapid stability during deceleration become more similar to those in high-velocity agility movements.

Variability Changes:

- Provide as many variances in movement

- Give athlete largest “movement bank”

Now in the last progression of the series, the athlete is now a proficient mover and stabilizer upon impact in each of the cardinal planes of movement. Coaches can now add variability within the system. By creating these minute variations in the execution of movements, a coach is able to add to an athlete’s “movement bank”. No two movements are ever completed in an identical fashion. This being said, an athlete will make a more efficient choice when said athlete has more to “pull from”. This theory explains why multi-sport athletes are able to move so much better than athletes that specialize early on. These athletes have an increased “movement bank” to pull from so they are able to effectively select the method in which they complete the desired action. Although small tweaks are being added to these movements hip stabilization must remain the most important aspect of training.

These are the concepts I have deemed valuable in the learning process my athletes go through. Coaches may disagree with my concepts themselves, or in regards to their order I place them and that is alright. I am simply laying out the thought process I use when creating a progression for my athletes based on my current understanding of the nervous system and tissue response. The important piece is that you select concepts that fit the model you implement, and then ensure the exercises selected achieve your desired concepts within an appropriate timeline.

Example Progression Implemented

Listed below is an example progression I have used with athletes. It is important to note that this is simply the exercises I have utilized to accomplish the concepts I have determined as important in the skill learning process. Again, if the concepts you choose to implement are different than mine that is alright, just know the exercises selected and/or their order will be altered compared to this example.

Neural Strategy Exercises:

- Glute iso work for plasticity

- Repeated hip stability

The glute isometric training is the method utilized to achieve “plasticity”, which is achieved through time under tension. The goal is 15-20 min of continuous activation. The series I have implemented, along with its concepts, can be seen by following the link here: http://vandykestrength.com/pages/glute_layer_intro. These are likely not new exercises to many. However, the requirements to achieve plasticity or increased neural drive are increased when compared to the normal “glute activation” exercises.

Increase Stability Exercises:

- Eccentric Valslide 4-Way Hip

- Eccentric Cable 4-Way Hip

- JOP Series DL Forward

- JOP Series SL Forward

- JOP Series SL Lateral

Keeping in mind the goal of this phase is to “groove” appropriate movement patterns, initial coaching is critical. As the athlete becomes more aware of the desired action to be completed, the level of coaching required should decrease. Each of these exercises require different levels of stability and can be progressed through in the order listed (top to bottom), with each one becoming more demanding on the stability required at the hip. The double leg jump and land can be incorporated early for increased support and learning prior to requiring a single leg to absorb high levels of force.

Force-Vector Change Exercises:

- JOP Multi-Directional

- Change Length of Jumps

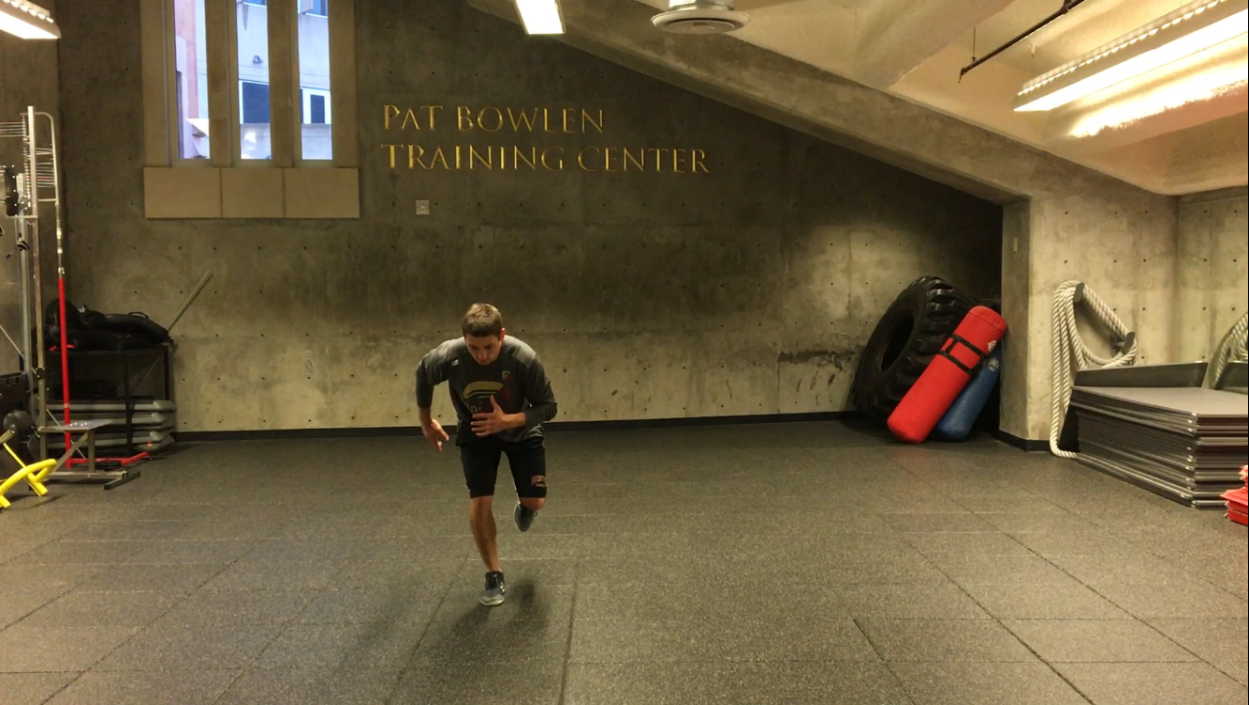

At this time the athlete is able to demonstrate the ability to absorb high levels of force on a single leg and can begin to move to a greater extent while maintaining stability when landing. This can be viewed in the two pictures below. The first simply demonstrates the start position, just as all of the previously hyperlinked exercises. The second shows the ending position for this movement. In this scenario the athlete is completing a 45o JOP at a moderate distance.

Starting Position for 45o JOP

Completion Position for 45o JOP

As the athlete progresses, distance can continually increase until maximal displacement is achieved. Remember, stable landing on a single leg must repeatedly be accomplished. The tiles on the floor allow for simple tracking of distance covered during jump movements and creates a clear progression as seen fit by the coach. The athlete should continue to achieve maximal height for each movement in accordance to their horizontal displacement. As the distance covered increases, height must decrease, but on shorter distances the athlete should still develop maximal force when leaving ground to require force absorption upon landing, which is critical for controlled deceleration, and thus lowers the likelihood of injury in movement. The simplest method to allow creativity is to treat the floor as a clock, force athletes to move in any direction while sticking the landing in an appropriate position.

Variability Change Exercises:

- Inside and outside leg

- Change of distance within set

- Add change of direction out of “stick” eventually can make reactive

In this final phase of progression, coaches are only limited by their athlete’s ability to stabilize through the hip, and then their own individual creativity. Force athletes to land on each of their legs regardless of the direction traveled. This is demonstrated in the 45o JOP with opposite foot stick below. In this jump, the athlete now must decelerate with their inside leg, driving a new requirement of the hip to stabilize as it prevents excessive valgus stress at the knee. By training the athlete to control in this position, they now have that movement strategy available should they experience it in competition.

Starting Position for 45o JOP with Opposite Foot Stick (Same as previous)

Completion Position for 45o JOP with Opposite Foot Stick

Again, in this phase the coach is ultimately limited by the ability of their athlete and their own imagination. By considering the athlete to be in the center of a bulls-eye on the floor, coaches can require changes in direction traveled, distance covered, rotation in air, opposite foot landing, etc. The options are truly endless in this setting, with each new repetition providing a new addition to their “movement bank” the athlete becomes well-rounded in multi-directional hip stability. With the understanding that change of direction is a primarily a series of horizontal decelerations and re-accelerations, coaches are able to alter distance covered during the jump to create a more specific force-vector. When these skills are mastered, a coach can even begin to add an immediate change of direction upon impact. An example of this is a 45o JOP with an opposite foot stick (as demonstrated above) with a single leg, vertical hop immediately following the landing. As always, ensure athletes are appropriate in their hip stabilization prior to adding in these advanced concepts.

A majority of athletes will pick up on the skills required of the first two phases relatively quickly. Beyond that, athletes can spend countless training sessions in the more advanced final two phases as they are so open ended. It can almost become a game between coach and athlete as to see if the coach is able to reduce the athlete’s stability with a new pattern. Obviously there are many more skills required to be effective in agility and rapid change of direction so it is important coaches do not spend too much time in each phase. Each athlete may begin in a different spot progression wise. However, coaches are often surprised with how many “advanced” athletes struggle with simple hip (glute) isolation work. When a coach works through a progression with these concepts laid out (exercises are just examples of concept execution) an athlete will achieve efficient and safe movement patterns.

All elite level athletes require rapid agility and change of direction. As described earlier, this abilities require multiple aspects to be trained at a high level. If an athlete lacks the ability to stabilize the hip with each stride or deceleration, they will never achieve elite level status. Only when an athlete is able to consistently demonstrate triplanar strength and stability in a reactive setting will elite performance be possible.