Peaking the Back Squat in Track and Field

By: Cal Dietz and Matt Van Dyke

As a coach in track and field, it is essential to know the proper times to peak your athletes in their different abilities; this includes certain abilities developed through proper strength training in the weight room, such as maximal strength. Gains in maximal strength lay the foundation of performance that will increase an athlete’s power output and rate of force development, which are crucial to improving all of their running and jumping abilities. As a runner approaches maximal velocity, ground contact time decreases substantially. With this concept in mind, a runner must be able to apply the same force into the ground during a much shorter ground contact time if they wish to maintain their velocity. There are many methods of improving power output and rate of force development, but one of the foundational approaches to increasing these potential abilities in sport performance is making gains in maximal strength, or 1RM, particularly in the back squat.

An athlete must increase their strength levels before they have the ability to increase their power outputs. Improving the maximal strength of an athlete in any movement allows for greater force to be produced across the entire force-velocity curve for that movement. This knowledge can become especially important for improving ground reaction force in running by utilizing the back squat. An increase in the 1RM of the back squat allows a runner to produce more force through the ground, even as the ground contact time becomes significantly lower at high velocities.

The utilization of the modified undulated triphasic training not only improves the function of the stretch-shortening cycle, but also increases maximal strength. This program lays the foundation for increased power output and rate of force development. Based on the competition date there is a proper time to peak maximum strength of the back squat within triphasic training. This proper time occurs within the concentric phase of training. The concentric training is the final phase of the triphasic model, meaning it occurs after the stretch-shortening cycle has been improved due to the eccentric and isometric training phases. The improvement in the stretch-shortening cycle allows the maximal amount of weight to be lifted through the dynamic motion of the back squat. This increased ability is the reason that the final week of the concentric phase is the optimal time to peak the back squat in triphasic training.

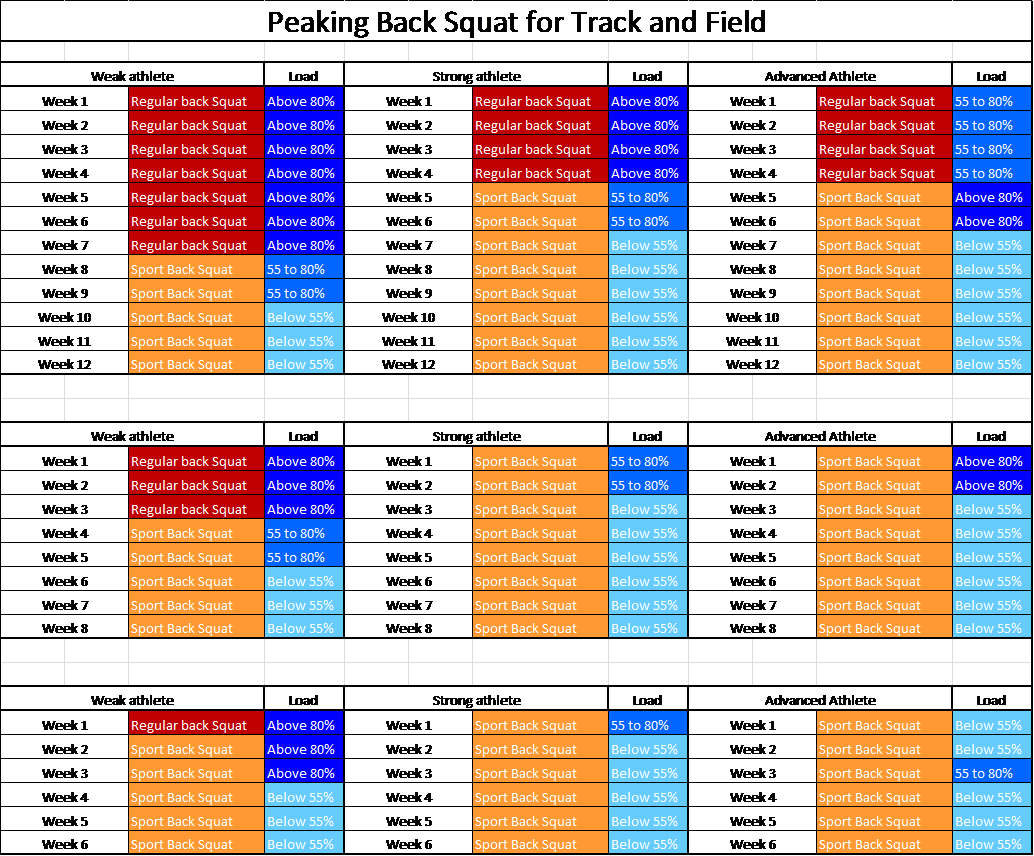

With the increased residual effect of maximal strength, the maximum strength of the back squat can be peaked, and maintained, at this time leaving enough training time to utilize the “55-80” and “below 55” phases properly before the competition event. The residual effect of training is the length of time that an ability, such as maximum strength, can remain adapted before decreasing back to its pre-trained levels. Maximum strength levels have a residual effect of 30+5 days. This allows more than enough time to add more track specific training to lifting sessions such as improving power output and rate of force development in your athletes. These adaptations are necessary for success and can be further peaked through the use of the sport-specific back squat, and high velocity training

The sport-specific back squat is executed with the feet directly under the hips. This causes the squat to be much more sport-specific as the force is transferred into the ground directly beneath the hips, the same way force is transferred in running. Your athlete’s strength levels will determine when the transition to a sport-specific back squat should be made since there comes a time as athletes become more advanced that sport-specific speed strength is more important to absolute strength. For this reason, your advanced athletes should utilize this more specific squat through the entire duration of training. For less advanced athletes, you have two options when applying the sport-specific back squat. First, you can treat these athletes just like well advanced athletes and allow them to peak using the sport-specific back squat through the entire phase. A second option for less advanced athletes is to make the transition a few weeks before competition in order to increase specificity. This will allow greater increases in strength because a normal back squat is used during the majority of training.

By increasing the strength of your athletes and improving their stretch-shortening cycle used in the back squat, they are given a greater ability to produce power and force quickly into the ground, especially during the acceleration and transition to top speed phases. Once maximum strength has been trained and the competition approaches, it is necessary to peak power outputs using the idea of high force at high velocity. This can be done using either a normal back squat, or the sport-specific squat, depending on the needs of your athletes as previously discussed. Power is determined by multiplying force and velocity together, so the faster the bar in the back squat is moved, the higher the power output of your athlete. It has been shown that when loads below 55% of 1RM are used, the resistance is too low to generate high power outputs, while loads above 80% of 1RM decrease the velocity of the bar, thus lowering power outputs for athletes. Keep in mind there is a difference in power outputs and high loads between most athletes and elite power or Olympic lifters. Power and Olympic lifters have the ability to produce power at heavier loads than athletes, but this skill alone does not make them elite track athletes. With these important findings in mind, the 55-80 block was created and is used to maximize power with high force and high velocity. The loads between 30%-50% are used to improve the velocity of the contraction while higher loads near 80% are used to recruit high threshold motor units that allow high power outputs. High-quality neural work is of vital importance in this stage as well. If the repetitions are set too high your athletes will be training work capacity due to neural fatigued factors, rather than peaking power output. It is important to note that power outputs begin to drop after the third repetition in a set. Biometric training can also be applied in this block to ensure all athletes are receiving the necessary stress to see adaptations, while guaranteeing none of them become over-trained.

After maximum strength and power outputs have been optimized and competition approaches, it is important that your athletes learn how to use their new increases in power. This is done by continually adding specificity to exercises in your strength and conditioning program, which will increase transferability of training to their specific event. When a specific exercise, such as the back squat, is progressed through an entire cycle, the training transfer to sport is much higher. The below 55 block uses high velocity peaking and trains your athletes at speeds just below, just above, and at the exact speeds used in track and field.

With these processes in mind, the squat jump can replace the back squat for continued sport-specific peaking. The squat jump has an increased transfer of training due to its specificity to track events since it uses a similar range of motion to the squat while implementing the power output and rate of force development necessary for maximal velocity sprinting. It should be noted that the range of motion of the squat jump should be modified to replicate the specific event for each of your athletes. The below 55 block is necessary for peaking, particularly for advanced athletes, who no longer see improvements in their event when increasing maximal strength due to minimal ground contact time.

The antagonistically facilitated specialized method of training (AFSM) also can be utilized in this high velocity peaking phase. The AFSM is used to train the antagonist muscle to relax more rapidly, allowing faster contraction. Once again maximal strength and power output levels make this high velocity, high transfer of training possible, so the first two phases using the barbell back squat set up this process.

The peaking of the back squat from maximal strength to sport-specific training is vital for increasing power output and rate of force development, which are absolutely necessary in maximum velocity running and jumping. Peaking maximal strength lays the foundation for power output and rate of force development to be further enhanced when using the sport-specific back squat, the 55-80 block, and below 55 block. The sport-specific back squat can be applied to further increase the applicability of the back squat to athletics. This increased specificity allows for greater force application just beneath the hips, which will further improve performance resulting from the peaking of the back squat. The 55-80 block continues to enhance power outputs using high force at a high velocities, while the below 55 block allows for high velocity peaking and continued improvement of rate of force development, which is the most crucial factor in track events due to ground contact time decreasing, as maximal velocity increases.