Supramaximal Slow Eccentrics and the Safety Bar Split Squat

By Cal Dietz and Matt Van Dyke

The Triphasic Training method is implemented with one goal in mind, STRESS. Stressing the body often, and in a different manner each training session, should be the goal of every strength coach to achieve optimal adaptations from their athletes. The stretch-shortening cycle (SSC), which is utilized in every dynamic movement, consists of an eccentric, isometric, and concentric phase and is the one of the most important ability in sports in terms of athlete power production and efficiency. Stressing the body specifically in order to maximize muscle and SSC force output is the ultimate goal of Triphasic Training. By training each of the three phases seen in every dynamic contraction separately, these three phase are maximized in their force absorbing and producing capabilities on an individual basis. When trained appropriately, this specific, individual training leads to an enhanced power transfer and efficiency in every movement completed in athletics.

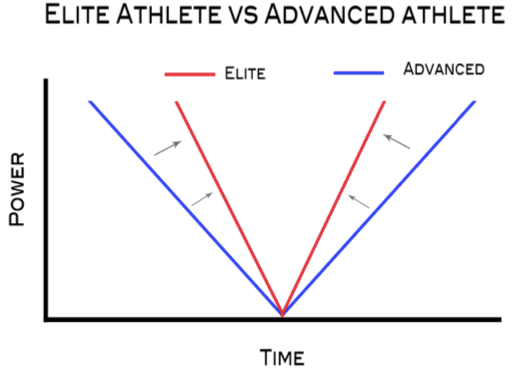

The eccentric phase of movement is vital for deceleration of the body. It is necessary to train the eccentric movements as the body cannot produce what it cannot absorb. In Figure 1.1, the left line is eccentric, or absorbing force, and the right line is the concentric, or force producing capabilities of an athlete. The isometric phase occurs briefly between the eccentric and concentric phases. This concentric action commonly gets all the glory in athletics, but when we look more closely, the importance of the eccentric and isometric phases becomes more apparent. When these three phases of dynamic contraction are combined, the “V” shape is formed. Based on our understanding of the SSC and the force producing capabilities of the muscles, the concentric portion of this “V” will never be steeper than the eccentric portion. By improving an athlete’s ability to absorb force eccentrically, the concentric, power production aspect is maximized, leading to improved sports performance. It becomes clear the elite athlete has an advantage based on their ability to absorb and produce force in a much more rapid fashion, while also working more efficiently with a higher percent of this power coming from the elastic components of the SSC.

Figure 1.1 – Force absorbing and producing capabilities

Specific, Supramaximal, Eccentric Training:

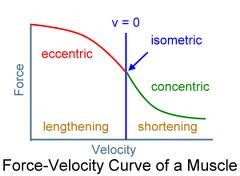

Now that the importance of improving the eccentric component of dynamic muscle contraction is better understood, it is necessary to cover how this specific phase can be maximally trained. Figure 1.2 displays the force-velocity curve of a muscle based on the phase being completed. It can be seen the eccentric component of movement has a much higher force producing capability than both the isometric and concentric muscle actions. A back squat is a simple example of this, an athlete is capable of using much more weight if they are only required to slowly lower the bar to the bottom position than if they were required to stand back up with the weight.

Eccentric muscle actions are not only stronger than the isometric and concentric phases, but they also function differently on a physiological level. The brain, specifically the cortex, uses a different strategy for motor recruitment during muscle lengthening than muscle shortening. During eccentric movements, the motor pool is less activated, leading to fewer muscle fibers being activated. The fact that fewer motor units are activated means there are fewer myosin head attachment sites during this eccentric movement phase. These fewer myosin-actin attachment sites lead to increased stress on those filament attachment sites that are being used.

This figure and example solidify the training mechanisms used within the Triphasic Training System to specifically train the eccentric phase of any muscle action. In order to train the eccentric movement phase maximally, which is the main goal of this method, loads must be high enough to stress the eccentric phase. It is with this idea in mind that supramaximal loads were implemented in the training of the eccentric block. Supramaximal loads must be used if the eccentric muscle action phase is to be stressed and improved to the greatest extent.

Figure 1.2 – Force-velocity curve of a muscle

Eccentric movements cause both muscle fibers and tendons to absorb high amounts of force as the muscle fights being lengthened. Due to the different recruitment pattern seen in eccentric movements, along with the supramaximal loads utilized, the stress on each myosin-actin structure is increased to an even greater extent. This increased stress will ultimately lead to microscopic muscle damage and athlete soreness, especially if the supramaximal training model is used (1). By applying maximal stress on the muscle fibers the body adapts accordingly and strengthens both the myosin-actin attachment site as well as the tendons utilized. Once the fiber has been rebuilt, the body has now adapted and prepared itself optimally to handle the stress of eccentric movements. The hormonal response of the body is also maximized when the high stress levels of supramaximal training is applied. This increased hormonal response continues to enhance the adaptation processes occurring within the athlete.

When appropriate stress and adaptation is applied in eccentric training, the movement now has an overall improved and more rapid eccentric movement. Improving the eccentric, or force absorption, phase leads to an increased storage of “free-energy” via the SSC within your athlete’s tendons throughout this phase. The muscle damage from supramaximal eccentric movements will cause soreness in the muscles, but once the soreness subsides, a strengthened and rebuilt muscle fiber remains. The muscle fiber and tendons have now been maximally trained eccentrically within the dynamic muscle contraction phases and the athlete is now prepared to handle the isometric phase of the Triphasic Training Method.

The isometric and concentric phases, combined with this training, will allow that “free-energy” from the SSC to be applied to all sport-specific movements. The supramaximal training of the eccentric phase leads to the creation of the steepest “V” possible for every individual athlete. It should be emphasized here this supramaximal eccentric training should be used only with highly advanced athletes that have a spotter on each side of the bar to assist in the concentric phase, as the load will be too high for the athlete to complete the rep on their own.

If we return to Figure 1.1, it is realized the two “V” graphs shown are actually the same athlete. The difference being pre- and post-supramaximal training. The supramaximal training will lead to the “V” becoming even steeper, or more compact, leading to greater free-energy utilization from the SSC. Not only will your athletes produce more power in less time, they will be spending less energy with every movement due to an improved SSC.

How to Apply Supramaximal Eccentrics:

We have chosen to apply supramaximal eccentrics in a unique way while training our athletes. The hands assisted, safety bar split squat has emerged, to this point, as one of the best ways to stress the body. This exercise turns a lower body movement into a unilateral, total body movement. The split squat portion allows individual leg training, which is vital for increased sports performance as athletics movements are completed dominantly using a single leg. By training with a single leg method, axial loading is also reduced while stress placed upon the individual leg muscles is increased. Adding the safety bar allows the athlete to train without using their hands to hold the bar on their back. By freeing the arms, the athlete is allowed to assist with the split squat by using their upper body to support and grasp the bar set out in front of them. The support of the arms also takes balance out of the equation as supramaximal loads are being used. Increased support and the use of the arms allows for even more weight to be used than a barbell split squat would allow, leading to even greater stress being applied to the entire body. The use of the arms, along with the increased load, stresses the core to an even greater extent than a barbell split squat. Supramaximal eccentrics using the hands assisted, safety bar split squat creates total body stress, engaging the arms as well as the core to improve the musculo-tendon structure maximally. The nervous system is also maximized through this supramaximal training, which is not the main focus of this article, but necessary for absolutely vital for improved athletic performance.

Supramaximal eccentric exercises, such as the hands assisted, safety bar split squat described above, should only be used in the first training block of the day. Using supramaximal loads for multiple exercises, or too many sets within a single training session, will cause too much stress to be placed on the body, actually leading to decreases in performance or injury. Supramaximal eccentrics can be used as potentiation exercises and can be completed prior to plyometric methods, such as the French Contrast Method. A key positive aspect of supramaximal eccentric training is that it can be applied to the exercises you are already using within your program.

Coaching Points:

While completing the hands assisted, safety bar split squat, focus must be placed on the back, chest, and leg positions. Keeping the back neutral, in a supported position, with the chest up will ensure that the lower back is well protected against harmful injuries. The front leg position should be around 90-90, with the back leg at an angle slightly extended beyond 90 degrees. It is important to make sure the back leg does not get too extended. If the leg becomes too extended, the athlete’s hips will begin to be pulled out of position and cause unnecessary stress. The athlete will move in a slow, smooth, and controlled fashion through the entire range of motion during the timed set. Breathing throughout the set also will be important to complete these heavy loads. Belly breathing can be used to increase intra-abdominal pressure and is the preferred breathing method. A spotter will be required as the supramaximal loads will be too heavy for the athlete to lift concentrically on their own. We suggest a spotter on each side of the bar as we have athletes nearing 600 lbs on the eccentric phase of the hands assisted, safety bar split squat. Even though the weight will be too heavy for the athlete to lift on their own, they will still focus on exploding up once the eccentric phase is completed.

Eccentric strength is a necessary component of every dynamic movement and is required to decelerate the body. The eccentric phase of contraction also plays a key role in the functioning of the SSC. The stress on the body from supramaximal, slow eccentric movements causes this first phase of every dynamic contraction to be optimally adapted. Maximizing the eccentric phase is an important first step to increasing power and efficiency in any desired movement, which ironically is missed in “typical” concentric training. Supramaximal, slow eccentrics cause damage to the muscle fiber heads but, in turn, lead to the body reconstructing those muscle attachment sites, creating a stronger, more resilient fiber. The use of the hands assisted, safety bar split squat leads to maximized stress placed on the body in training, which leads to enhanced adaptations, and ultimately maximized performance. Once the eccentric phase of Triphasic Training has been completed, the athlete is now able to move into the isometric training phase. As a performance coach, always remember Figure 1.1, the steeper the “V” becomes, most specifically eccentrically, the more powerful, explosive, and efficient your athletes have the ability to become.

References:

Maughan, R., & Gleeson, M. (2010). The Biochemical Basics of Sport Performance (2nd ed.). Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.